“Evolutionary Architecture”

SunRay Kelley Builds Rather Nice Looking Buildings. Getting All The Right Permits Is Another Matter.

Words by Patrick Pittman

SUNRAY KELLEY, LIKE NATURE, ABHORS A STRAIGHT LINE.

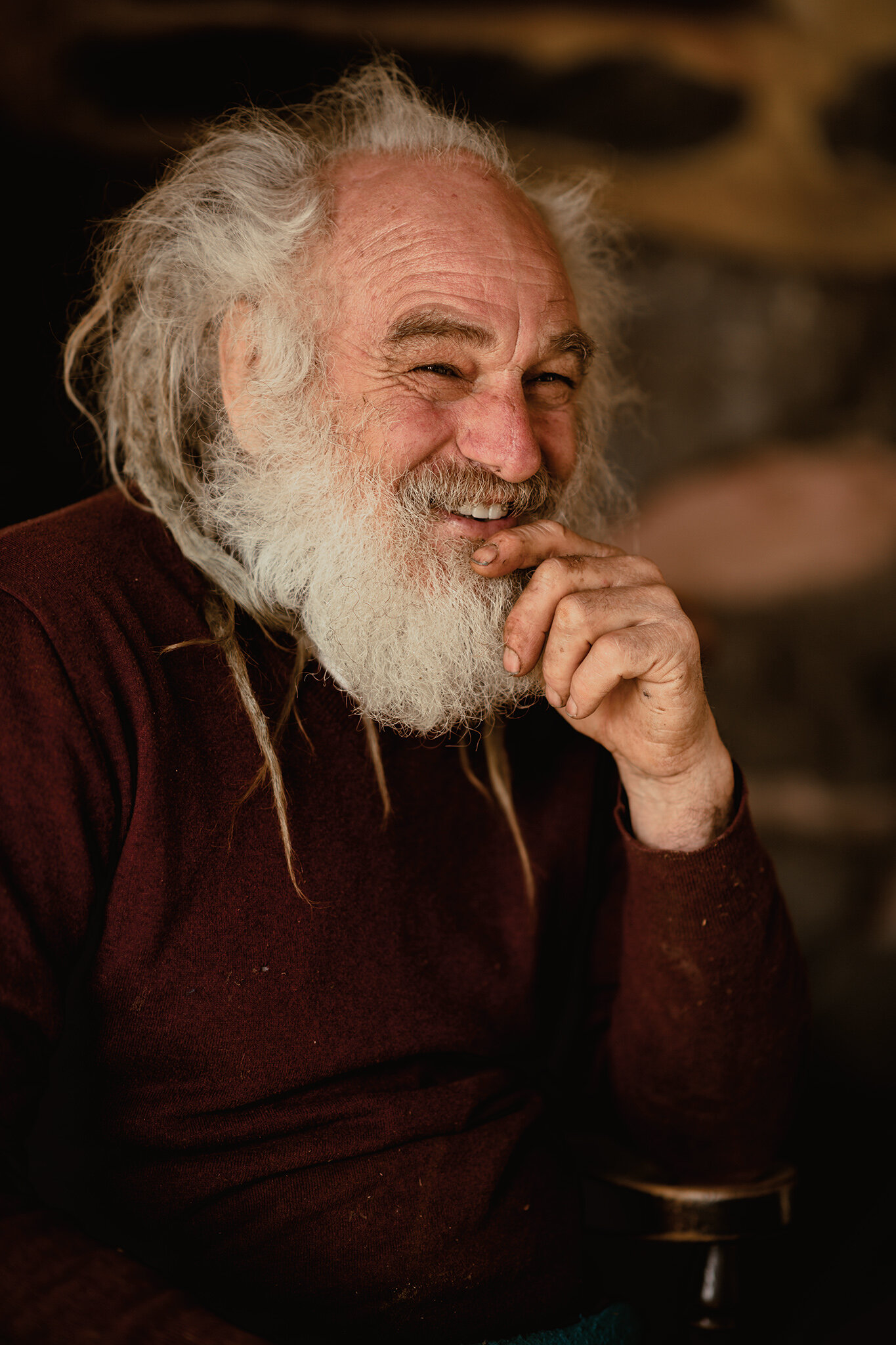

It’s a crisp spring day and the architect is sitting in the sun in the only place he’s ever called home – his nine-acre property near Sedro-Woolley in northern Washington state. It’s a natural wonderland and, effectively, a gallery of his most distinctive works – treehouses, yurts, ponds and temples constructed with the materials offered up by the land around.

Kelley has built his Shire largely with his own hands, and with the hands of those who’ve passed through over the decades, from partners and acolytes to Airbnb lodgers. The swooping timber curves, incongruous parapets and overgrown living garden rooftops of his many constructions bring to mind the turf houses of Iceland if they’d been rethought by Antoni Gaudí in a lesser-known lumberjack phase, when he’d lost his mind working on a commission for a mystic woodland sprite.

“I go out in the real world and collect the materials I want to build from,” Kelley explains, pointing towards an overhanging fir silhouetted against a blue sky. Where conventional architects talk in terms of right angles and load-bearing materials, Kelley, who considers himself a “natural architect”, starts from somewhere a little… looser. “I call it the supernatural market,” he says. “I work with nature, because natural materials have an embodied energy in them that’s giving. A natural home will give energy to you all of its life.”

Kelley uses the word ‘energy’ like the unashamed hippie that he is. That might trigger a little skepticism, but the truth is it’s hard to resist the unfiltered drive of his work and his own, well, energy. It’s not just uncut hokum from the Age of Aquarius. Consider it a barefoot manifestation of what Frank Lloyd Wright was getting at with his longing for “organic architecture” back in 1939. Wright envisioned a world where architecture sprang out of nature rather than in sharp opposition to it. To that end, Kelley sees Wright’s Fallingwater and raises him a ramshackle, four-story, hand-hewn Sky House.

When we speak, Kelley is sitting in front of a building he calls The Temple, describing how he loves to curve and shape the materials – a dance, he says, “between the masculine and feminine” that pulls his structures into their ultimate forms. When he is building structures for clients in places as diverse as Oregon and Costa Rica, Kelley throws himself into research about what the lan has to offer him there. Here at home – where his grandparents first homesteaded in 1920, where his father raised cattle, where, as a boy, Kelley learned to build by taking things apart and putting them back together, and where, after his father died, Kelley tore down the fences and replaced them with fruit trees to grow an “edible forest” – he knows what’s under every stone, where every root runs, and where every creature burrows its home. It’s listening that drives the process.

“I practice what I call evolutionary architecture,” he says, “which means I don’t know exactly where it’s going. I’m open to what’s going to come along the way, and what materials will show up that might be different than what I had originally planned. I will change my plans from time to time and do it differently. That creates a huge problem with the permit people.”

He tells me the ways materials communicate, what the trees and rocks can tell him. He says we’ve forgotten how to hear nature. Who, I ask, has the patience to commission an architect who can’t build to plan, let alone to explain that to a council bureaucrat? “The crazies,” he laughs. “The nuts people. Not the normal people. It’s interesting who comes and why. A lot of people love my work but want me to tone it down. I get too wild for a lot of them. In general, most people shy away because it’s not their idea of what a house is supposed to look like.”

He breaks off and starts singing: little boxes, on the hillside, little boxes made of ticky tacky. “You know that song?” I join in, little boxes all the same. “You know,” he continues, snapping back to the point after making a little fake vomit noise, “I want my work to be jaw-dropping. I want people to have an out-of-the-ordinary experience when they see my buildings.”

The frequently barefoot architect sees his work as a collaboration with nature: a way to repair the severed connection that has pushed us to the environmental and existential brink. We’re not separate from nature, he explains. We are nature. “We may survive this sixth mass extinction, and we may not,” he says, “but I feel like we are the stupidest animal on the planet. It’s just unbelievable for me the way we treat the air, the water, the earth. Our arrogance and our thinking we’re somehow the smartest creature. The planet will go on; whether we survive as a human species or not, I’m not sure.” He pauses this apocalyptic train of thought and turns to his partner Bonnie Howard, who’s weeding behind him. He’s noticed what she’s working on, and shouts that she better not pull the wrong plants out. “I know!” she shouts back. “Relax.”

Unlike the metallic skyscrapers that dot Seattle’s nearby skyline, Kelley’s structures are designed to mimic the organic objects hey are built from. And like any organic being, his houses sometimes die. One of his most famous works was the temple at the Harbin Hot Springs, a mecca for New Age seekers and burnt-out Silicon Valley workers. That temple, though, was destroyed by the ferocious Valley Fire that tore through Northern California in 2015.

“That was really an amazing building,” he sighs over the rising sound of croaking frogs. “Nothing lasts forever, they say, so you’ve got to accept that. It’s all temporary in this world. Ideally it would last thousands of years, though that may be my ego talking.”

For Kelley, the drive to create is relentless, however impermanent the result. With the land at Sedro-Woolley now as full as it can be, and given his minimal desire to commute to the outside world, he is turning his attention to more portable forms of practice. These include converting trailers and old campers into more environmentally friendly ‘gypsy wagons’ with his distinct aesthetic, and experimenting with electric vehicles to get his entire property off the grid and on to solar. “If you have a gift and you’re not giving it, well, you’re not really living your life as you should be… Sometimes we forget that we’re just part of this huge, vast life happening all around us, and we don’t even see it.”

Kelley’s buildings might be driven by the vernacular instinct of an esoteric old hippie, but they’re something else, too – a reminder that in the face of environmental calamity, the normal way to live isn’t just boring; it’s actively destroying us. “We’re lost in the concepts that aren’t really serving us anymore,” he says. “We have a lot of old ideas that really hold us back from being allowed to find our true nature.”